The cat fine problem – origins and risks

The shipping industry is used to large-scale challenges, from the complicated logistics of global trade to the risks posed by storms and waves. Yet one of the biggest threats it faces are the tiny particles known as cat fines. Cat fines in residual fuel oils are a significant danger if not effectively removed, and the first step in combatting them is to understand their origins and potential for harm.

What are cat fines, exactly?

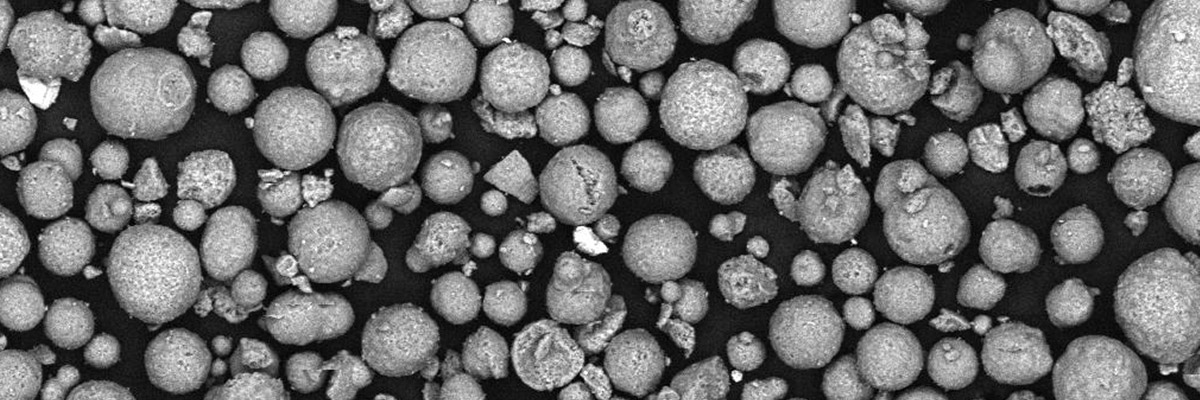

‘Cat fine’ is short for ‘catalytic fine’, a type of microscopic particle left in residual oils after refining. Modern refineries use atmospheric and vacuum distillation first, which extracts the most volatile, higher-value products from the top of the distillation column. Afterwards, they rely on thermal and catalytic processes to divide the remaining crude into additional fractions. Catalytic cracking uses synthetic crystalline zeolites – porous mineral compounds of aluminium and silicon – to break up the stubborn oil molecules.

Inevitably, some of the zeolite catalysts make their way into residual oil products. The fine particles vary in size from the sub-micron range to around 100 microns, or roughly from a speck of dust to the width of a human hair. Their density varies as well, and while larger particles may settle in oil, smaller cat fines with lower densities may remain suspended in the fuel.

Most critically, cat fines are abrasive and extremely hard, measuring up to 8.2 on the Mohs scale. This is hard enough to scratch or become embedded into steel surfaces – especially those between the moving parts of marine engines.

The damage that cat fines cause

When cat fines make it past protective systems and through the engine injector, they can become trapped between the piston ring and the cylinder liner – a gap measured in microns. With every stroke of the piston, the fines are ground into the smooth surfaces, carving tracks that build up over time. Abrasive damage can occur not only in the cylinders, but also in the injectors and in components such as fuel pumps and valves.

Even the smallest particles can cause significant harm, and the risk is not only long-term mechanical wear and tear. In high concentrations, cat fines can cause acute, catastrophic damage in a remarkably short period of time.

One report available online describes a cat fine attack that crippled an engine in just 100 hours of use. When the engine was stripped down, engineers found that “all pistons and liners were totally destroyed and had to be changed.” As reported to CIMAC, MAN’s PrimeServ team implicated cat fines in 190 of 226 cases (84%) of cylinder liner damage during a three-year period.

Repairing such damage is extremely expensive, with reports of claims ranging from 300,000 to 1.5 million US dollars. This makes cat fines a headache not only for shipowners and operators, but also for those who insure their vessels.

A problem that persists

Reports of cat fine damage have long been a fact of life in the marine industry, appearing first in the 1980s. Rising oil prices in the 1970s had led refineries to expand their use of catalytic cracking, in order to extract more valuable products from the available crude. But even more intensive cracking is required to meet today’s marine fuel sulphur limits, which means the process is more prevalent than ever – as is the cat fine risk. Worse still, as new catalysts are implemented, they may lead to even harder cat fines.

Since the catalysts themselves are expensive, one might expect refineries to do more to keep them out of bunker fuel. In fact, refineries recover and reuse as much of the catalyst content as they can. Beyond a certain point, it’s no longer practical or economically feasible for them to try harder.

In other words, the cat fine problem will remain. If anything, the cat fine levels in fuel are growing even less predictable, both in the bunkers themselves and as a result of fuel blending. What is certain is the importance of an effective fuel line that can adapt to fuel variations, even as the fuels on board change.